The 20th Congress of China’s ruling Communist Party (CCP) has further consolidated the power of the party-state over society, with President Xi Jinping at its head. Xi has formally inaugurated his third term as supreme leader of the country – a feat only matched by Mao in the history of the People’s Republic of China. The senior leadership of the CCP is now entirely staffed by Xi’s trusted lieutenants. The heavily-stressed theme of this Congress was the necessity of the party-state’s leadership as the country enters the coming period.

In China, where capitalism is administered by a self-proclaimed ‘communist’ bureaucracy, the Congresses of the CCP are the most significant political events the country witnesses.

This year, the Congress opened amidst the most serious economic and social crisis China has witnessed in decades. The slowdown of economic growth, the massive social anger over the draconian COVID-19 lockdowns, rolling blackouts and crises such as Evergrande among many other issues are all eroding away at the stability of the CCP regime at an accelerating pace.

Mounting instability is anticipated by a decisive section of the CCP bureaucracy, and Xi Jinping is foremost among those championing the tightening of the party-state’s control over society in preparation for social explosions. The strengthening of Xi’s powers and those of the CCP in general reflect these growing contradictions in the depths of society. The 20th Congress is but a milestone in this process.

New leadership and utmost consolidation

At this party Congress, Xi Jinping laid out a general course for the bureaucracy in the form of changes to the party leadership, amendments to its constitution, and Congress documents released to the world. These are usually decided upon months in advance through secretive, backdoor jostling among the various party factions, with the resultant leadership composition and policy reflecting the balance of forces of the tendencies within the bureaucracy.

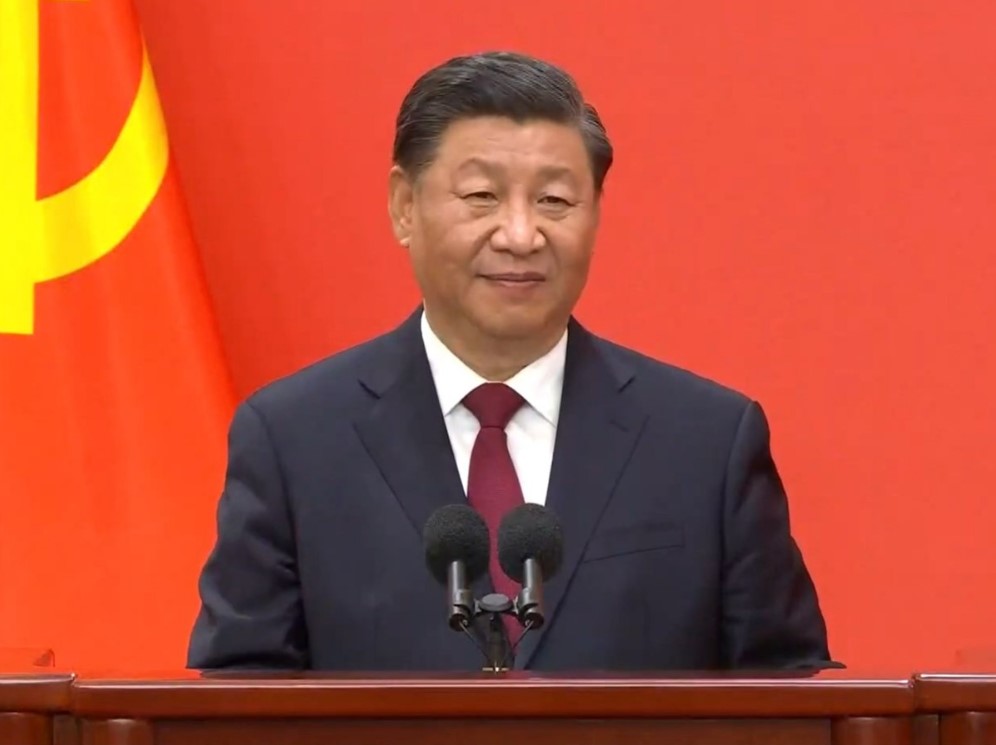

At this year's party Congress, Xi Jinping secured a third term as the country’s top leader / Image: 中国新闻网

At this year's party Congress, Xi Jinping secured a third term as the country’s top leader / Image: 中国新闻网

This year, Xi Jinping secured a third term as the country’s top leader. This was supposed to have been ruled out by Deng’s leadership following the death of Mao to prevent the emergence of another individual dictator in favour of collective leadership of the bureaucracy. The 20th Congress has put an end to this unwritten tradition, and Xi Jinping has now emerged as the very dictator that Deng and co. sought to prevent decades ago.

Indeed, a further ‘rule’ established by Deng has also been shattered: that of indicating clear successors within the top leadership. Among the new members of the Politburo Standing Committee (SC), there is no clear successor to Xi. Xi could very well be aiming for more terms in power, and perhaps even to become President for life.

None of this is surprising given that in 2018, Xi signalled his ambitions by forcing through a constitutional amendment abolishing term limits for Presidents and Vice Presidents.

But Xi’s concentration of power flows from the general need of the CCP bureaucracy to strengthen its own grip on power in the face of mounting contradictions within Chinese and world capitalism, as well as ferment from below. Xi convinced the party mainstream that only by centralising greater control over society and the economy can the party’s dictatorship, privileges and profits be guaranteed.

While Xi’s own position was a foregone conclusion, what the world was waiting to find out was the make-up of the Standing Committee (SC), i.e. the seven most powerful men in China who will rule alongside Xi for the next five years. Since Deng’s time, the SC has been more-or-less proportionally representative of the power of the various factions in the CCP, each keeping the other in check while ruling over the country. And, as mentioned, the SC would usually include a clearly appointed successor – often an individual in their 50s.

The new SC slate saw Xi completely upending that tradition. Anyone seen as a potential counterweight to Xi was removed. The body is now staffed entirely by his closest and most loyal subordinates.

The new SC removed powerful figures such as Premier Li Keqiang, Vice Premier Han Zheng, Chairman of the Political Consultative Conference Wang Yang, and head of the National People’s Congress Li Zhanshu. These figures, while already highly subservient to Xi in the previous five years, have been seen as a potential counterbalance to Xi’s personal faction. In recent times, Premier Li Keqiang has more-or-less openly clashed with Xi over the question of maintaining the harsh COVID-19 lockdowns across the country.

Notably, Li and Wang are also seen as the most openly pro-market elements within the top leadership. Their removal would indicate that Xi is fully aware of the turbulent period ahead for world capitalism and its inevitable impact on the Chinese market, which will require a greater role for the state in the coming period.

From the previous SC, Wang Huning and Zhao Leji have been retained. The former works closely with Xi as his chief propagandist, while the latter directed the anti-corruption campaigns that rooted out Xi’s rivals within the party. The new SC members include Shanghai Party Secretary Li Qiang, Beijing Party Secretary Cai Qi, Director of the CCP’s General Office Ding Xuexiang, and Guangdong Provincial Party Secretary Li Xi. Cai Qi and Li Qiang were Xi’s subordinates when the latter was governing Zhejiang Province between 2003 and 2007 and have been his staunch lieutenants. Ding Xuexiang already served essentially as Xi’s chief-of-staff in the last term.

In this way, the SC is now entirely staffed by not only people who are aligned with Xi, but people who have already worked as his henchmen. The same faction of people, often referred to as the ‘New Zhijiang Army’ (之江新军), who worked under Xi in his time in Zhejiang and since, also dominate the Politburo and the Central Committee. Other major factions, such as the Young Communist League or the Jiang Zemin faction, have completely lost their voice within the top leadership. With this new set-up, Xi is announcing to the Party, the country, and the wider world that his role in steering China’s future is nothing short of absolute.

Perhaps to drive this point home with some theatrical flair, an extraordinary public humiliation of Xi’s main rival faction took place as the Congress concluded. Former President Hu Jintao, perhaps the foremost representative of the Young Communist League faction, was originally next to Xi Jinping in the seating arrangement for the closing of the Congress. But only moments before the closing session, two staffers tried to pull him up like a rag doll before leading him out of the conference hall.

This episode transpired in front of the press. Footage of Hu’s departure clearly showed that he was surprised by the move and reluctant to leave. Xi looked on with an ice-cold stare. The proceedings moved forward after Hu vacated the premises, with Xi declaring Congress decisions next to an empty seat. Later, official sources claimed Hu departed because he was “ill”. The message is clear, however: Xi stands below no one in China, not even its former leaders.

Aside from changes of personnel at the top of the Party and state, the 20th Congress amendments of the Party’s constitution also signal important changes in the bureaucracy’s perspectives.

In yet another move to secure his position, Xi Jinping pushed through the inclusion of the ‘Two Establishes’ principle into the Party’s constitution. ‘Two Establishes’ (两个确立) explicitly declare that Xi Jinping must remain at the core of the Party’s leadership, while Xi Jinping Thought must become the guiding ideology of the CCP in the next period. This leaves no room for doubting that, everything else being equal, Xi intends to dominate the Chinese state for many years. However, there are many reasons to doubt that things will be equal.

Doomed ‘Reformism with Chinese Characteristics’

Another notable amendment of the Party’s constitution concerned extending control over the market economy, while curbing the growth of inequality. The amendment reads:

“…the system under which public ownership is the mainstay and diverse forms of ownership develop together, the system under which distribution according to work is the mainstay while multiple forms of distribution exist alongside it, and the socialist market economy, are important pillars of socialism with Chinese characteristics.”

This reflects the regime’s persistent fear that the increasingly volatile boom-bust cycles of Chinese and world markets now threaten the stability of the regime. Xi has explicitly ruled out ever returning to a planned economy. What this really sets out is the bureaucracy’s intention to intervene in the market to ‘correct’ the inherent contradictions of capitalism.

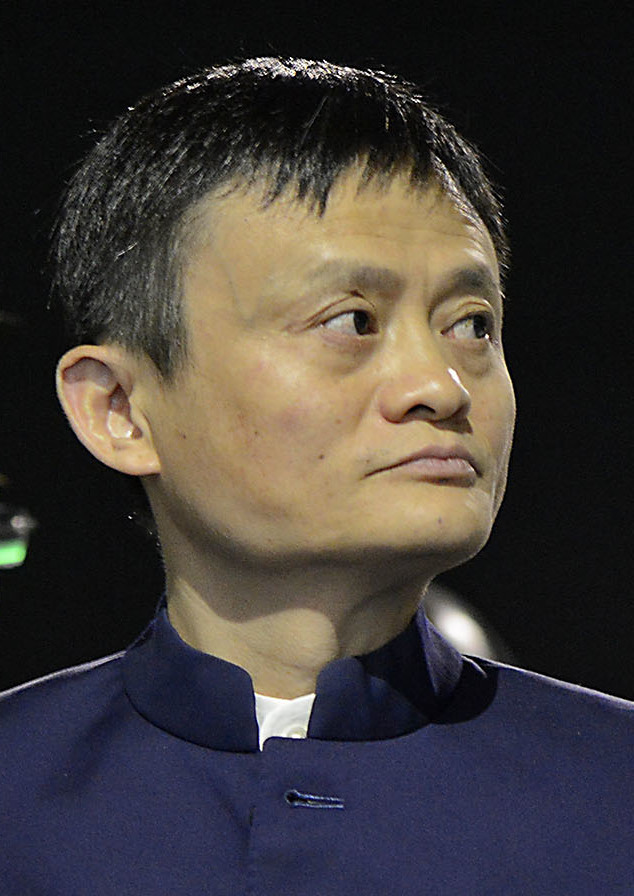

Xi has ruled out returning to a planned economy, instead choosing to intervene in the market; for example, by curbing the activities of capitalists like Jack Ma / Image: UNclimatechange

Xi has ruled out returning to a planned economy, instead choosing to intervene in the market; for example, by curbing the activities of capitalists like Jack Ma / Image: UNclimatechange

The powerful Bonapartist bureaucracy that exists in China has transformed the country over decades from a planned economy into a capitalist economy, whilst retaining a powerful state sector. It nurtured the development of the market and it continues to believe that it can call the shots. But the dynamics of the capitalist economy are outside the control of the bureaucracy or of any individual capitalist upon whose head the bureaucracy may bring down its ‘discipline’.

Capitalist development in China over the past twenty years was extremely rapid, achieving in that time a level of development that Western economies required over a century to reach. As a consequence of the lightning speed of industrial development, there now exists an overcapacity in production. Today, China’s industrial capacity utilisation rate continues to hover around 75 percent. By comparison, the rate of capacity utilisation in the United States stands at 79 percent.

These are classical symptoms of crises of overproduction, which Marx long ago explained. Glutted markets make productive investment less profitable, and as a result investment has increasingly been directed towards unproductive speculation. All of this shows that China’s crisis is rooted in the contradictions of capitalism – just like the West – irrespective of attempts by the CCP to disguise the fact or to attenuate these contradictions.

The growth of inequality – inevitable under capitalism – is also producing tremendous discontent among the Chinese masses. The Xi regime is conscious of this problem. Xi Jinping even recommended that party members read reformist academic Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the 21st Century in order to learn how inequality in the West has led to political instability. China’s attempt at countering this is to somehow redistribute wealth – once again, through the strong arm of the state.

However, it remains to be seen how exactly the CCP aims to do this. No concrete policies have been rolled out yet in terms of distribution, but stronger leashes have been placed upon private capital. Recently, big private capitalists and enterprises, above all Jack Ma, were curbed or punished for their wild levels of profiteering that were regarded as threatening the stability of the economy. The party-state has also deployed cadres in private ventures to influence their decision making, with the number of enterprises with party committees in their management having risen to over 1.6 million since Xi took power ten years ago.

Although the private capitalists have been called to order, China still has not instituted the kind of reformist measures we have seen in the past in some of the wealthiest capitalist countries. The Chinese tax system strongly favours the rich and heavily burdens workers. But any attempt to introduce a more common ‘progressive’ tax system would have the potential to destabilise an already unstable economy. For example, a plan to expand property tax in 2021 was halted as the Evergrande crisis came to the fore, amidst fear that new taxes could exacerbate market panic over China’s real estate sector.

Nonetheless, with the bureaucracy alarmed at rising inequality and social ferment, the strong arm of the state may attempt some degree of ‘wealth redistribution’. However, Marxists understand that such measures cannot eradicate the contradictions that China is facing. In fact such an attempt could even precipitate the economic crisis that the bureaucracy is desperate to evade. Any attempt to reestablish social equilibrium on the part of the state at this stage would severely upset the economic equilibrium. Indeed, the Hong Kong and Shanghai stock markets tanked at Congress’ close at the mere whiff that the CCP regime may at some point enforce measures that the markets view as detrimental.

The Xi regime dreams of creating an ever-growing capitalist economy that is perfectly managed by the state. In his opening speech for the Congress Xi reiterated the “two unwavering principles” (两个“毫不动摇”), which stress that the state can at once guarantee the primary role of public ownership while fully encouraging the development of private ownership in a perfectly stable way. This is a fantasy, notwithstanding the forceful hand of the state in the economy. Chinese capitalism will continue to lurch towards the very same chaos that its counterparts in the West are already embroiled in, unless it is overthrown and replaced with a socialist plan of production based upon workers’ democracy.

The spectre of militarism

Another important point of focus in the Congress concerned the question of Taiwan. Many believe that Xi has ambitions to annex Taiwan, as it increasingly becomes a beachhead for the US in the inter-imperialist rivalry between the two powers.

Nancy Pelosi’s sudden visit to Taiwan in August was another provocation that tested China’s limits / Image: Wang Yu Ching Office of the President

Nancy Pelosi’s sudden visit to Taiwan in August was another provocation that tested China’s limits / Image: Wang Yu Ching Office of the President

In the Party Congress, the Taiwan question was given focus at two key moments. During his opening report to the Congress, Xi Jinping stated that China would “never commit to abandoning the use of force” as an option to annex Taiwan. In the very same report, Xi stressed the need for modernisation of the military as a necessary step towards becoming a “socialist strong modernised nation” (社会主义现代化强国). Later, the phrase, “against Taiwanese independence” was written into the Party Constitution.

The question of Taiwan has many important implications for the CCP regime as a whole. Domestically, ‘unifying’ with Taiwan has been a key promise of the regime, which has become increasingly reliant on nationalist demagogy. Any sign that the CCP is unable to do so would deal a blow to the credibility of its regime among the masses.

Internationally, the US is rapidly arming Taiwan as its frontline against China in its bid to contain the latter’s ambitions. This introduces a new urgency into the situation. This year, Biden has more than once explicitly stated that the US would militarily defend Taiwan. Although he has been contradicted by other Administration officials, the US seems to be stumbling towards abandoning its historic position of “strategic ambiguity”. Nancy Pelosi’s sudden visit to Taiwan in August was another provocation that tested China’s limits. The US military establishment periodically raises alarms about supposed Chinese plans to invade Taiwan, the most recent being Admiral Matt Gilday’s warning that China could invade Taiwan as early as 2023. These remarks are nothing but a cynical imperialist ploy aimed at rallying support at home in the name of “defending democracy”.

Despite the alarmism on the part of Gilday, the Chinese military is not as yet equipped to take over Taiwan within a year’s time. However, it is clear that Xi harbours ambitions of becoming the Chinese leader that annexes Taiwan. To achieve this, as well as meeting the growing need to protect the interests of Chinese imperialism around the world, Xi will have to hasten the strengthening of China’s military power in the coming period.

Militarism on all sides and the potential for war as a result of imperialist rivalry are therefore growing by the day. Pathetic appeals to the ‘rationality’ of the ruling classes on either side are completely hopeless. Capitalism as a system inherently pushes countries towards conflict, as the need to re-divide the world market arises among the great powers. Taiwan is but a chess piece in China’s quest to dominate Asia, and for the US it is the place where it intends to put a check on its burgeoning nemesis.

Economy on shaky ground

Xi’s third term governing China will be anything but the orderly affair that the Congress was presented as.

The Evergrande crisis stems from unsustainable corporate debt, but it is only a snapshot of China’s overall debt problem / Image: Windmemories

The Evergrande crisis stems from unsustainable corporate debt, but it is only a snapshot of China’s overall debt problem / Image: Windmemories

It is increasingly clear that Chinese capitalism is at the beginning of an enormous economic crisis, one that has been prepared by the growth of the previous decades. The disruptions of the COVID-19 pandemic only added to the strain that the Chinese economy is already under. Prior to 2020, the question of whether China was able to maintain GDP growth above 5 percent already provoked much anxiety for the regime. Yet today, the state is resigned to a growth rate well below 5 percent. The IMF lowered China’s growth forecast in 2023 to 4.4 percent. China’s own Caixin magazine predicts 2.4 percent for 2022 and 4.6 percent for 2023, assuming lockdown measures are eased after October.

If China ends up with a similar growth rate as that of the West, then there would be far more problems for the CCP. As the Atlantic Council pointed out:

“While advanced economies like the United States and United Kingdom routinely experience growth around 2 percent, such a scenario in China could lead to mass layoffs, a rapid tightening of credit, and, perhaps most troubling for Xi, a serious blow to his authority.”

Slowing growth and debt are the major threats to the Chinese economy. The unfolding crisis of Evergrande stems from unsustainable corporate debt, but it is only a snapshot of China’s overall debt problem. As of now, total national debt stands at 230 percent of China’s GDP, while the national leverage rate (debt/income) is at 273 percent. Average household leverage, a key indicator of how much debt affects ordinary people’s lives, now stands at 70 percent.

The state, which Xi hopes to use to manage the market economy, is itself in growing debt. The central government’s debt rate is said to be around 43 percent. However, regional debts vary tremendously. Deeply indebted provinces, such as Qinghai, Heilongjiang, Ningxia, and Inner Mongolia, had spending-to-income differentials exceeding 300 percent as of 2020. Furthermore, in an effort to revitalise the Chinese economy after harsh lockdowns in many areas, the central state has instructed regional governments to take drastic Keynesian measures to prop up the economy, pushing many provinces further into debt while placing a strain on the minority of provinces that generate net income for the state. The SOEs that play a key role in the Chinese economy, now have over 63.7 percent debt to total asset ratios. Debts are growing everywhere in China, and thus far the regime has not taken any measure that can curb them.

The Chinese model of capitalism has run out of road. Increasingly, it has been dependent on the property sector for growth. But this sector now has a debt rate of 75%, roughly the same proportion as the US property sector in 2008. Property construction has been the basis for local government finances, since 40 percent of their revenues come from land sales to developers. This in turn is enormously important, because it is local governments that are responsible for driving the rest of the growth in the economy, by lending money for infrastructure investment.

Property developers missed payments on a record $31.4 billion in offshore dollar bonds by August. This is because home sales collapsed by around 30 percent over the past year, driving many property firms to bankruptcy. As developers’ revenues collapsed, they slashed their land purchases for new projects. As a result, the land purchases local governments depend on are down 28 percent this year. This drying up of income to local authorities could destabilise their $7.8 trillion of debt (nearly half of Chinese GDP in 2021!), leading to a full blown economic crisis.

This mountain of unsustainable local government debt, and the speculative property boom associated with it, was piled up to rescue China, and the world, from a depression in 2008.

As we can see, there is no solution under capitalism that could once and for all resolve these problems. Low growth and debt are but the symptoms of the crisis of overproduction. No amount of consolidation of power in the hands of the state can possibly overcome them.

Decoupling

Internationally, the third Xi Jinping term will see a world rife with rivalries, protectionism and conflicts. Above all, China will be squaring off with a desperately belligerent US imperialism and its allies.

China realises the need to shield itself economically through decoupling from the international supply chain that is ultimately dominated by the West.

This is especially apparent as the US has sought to kneecap China’s tech industry through a microchip sanction introduced in October 2022. In response, China is making huge investments to achieve “microchip independence”. More broadly, China enacted a plan to replace all foreign-built computer parts in domestic facilities within three years. Chinese suppliers of computer parts for the Chinese market have increased their share of the market against foreign suppliers. Lenovo (57 percent) and Founder (15 percent) are now the primary suppliers, whilst Intel and Dell are in single digits.

China’s attempt at decoupling tech supply chains is part of a more general decoupling effort to shield itself from economic attacks from the West.

Similar efforts to decouple diplomatically have been made by the Xi regime. Unlike in pre-Xi years where China adopted an accommodating posture to diplomatic institutions dominated by the US, diplomacy under Xi is marked by harsh railings against the West (known as “Wolf Warrior Diplomacy”), with efforts to propagate alternative international institutions where China can rally support from other countries.

In the increasingly multipolar and unstable world, China under Xi Jinping will inevitably become a major pole against the US-led imperialist bloc. The Chinese working class will inevitably suffer in one way or another as the conflict among ruling classes of different powers deepens.

Struggle from below

The Xi leadership faces a world rife with uncertainty. The Chinese working class has suffered deeply in the past period, especially in the last two years. We have seen a correspondingly sharp rise in its willingness to struggle, especially among the youth.

Impressive feats of organisation such as the Henan depositors’ protests have drawn in thousands of people despite omnipresent internet surveillance / Image: Fair Use

Impressive feats of organisation such as the Henan depositors’ protests have drawn in thousands of people despite omnipresent internet surveillance / Image: Fair Use

The Chinese working class has suffered deeply from the harsh lockdown measures that the state imposed in its futile effort to maintain ‘zero COVID’. Millions of people’s daily lives are disrupted by constant orders to do PCR tests, while those unfortunate enough to contract the virus (and their neighbours) are subjected to poorly-administered quarantine centres. Tens of thousands have lost their jobs or have been furloughed, and food prices have skyrocketed in quarantine zones. Many who have been ordered to stay at home cannot properly access daily necessities.

These hasty measures taken by the regime without considering the mood of the masses quickly inspired mass discontent. Most of the time this discontent has been expressed through avalanches of angry sentiments on the internet that defy the harsh censorship rules. In other cases, impressive feats of organisation such as anti-government protests on university campuses or the Henan depositors’ protests have even drawn in thousands of people despite omnipresent internet surveillance.

Most recently, a lone man travelled to Beijing’s busy Sitong Bridge and hung up a banner that demanded the right to vote as well as a call for strikes to depose Xi Jinping. This man was swiftly apprehended by the authorities, but videos of his exploit spread even faster on the internet and garnered widespread sympathy from all over the country. A manifesto believed to be authored by this man has been circulated. While he appears to hold illusions that China could be reformed along bourgeois liberal lines, his act of defiance has inspired much discussion, and some have even drawn conclusions that go far beyond liberal democratic demands and move in a socialist direction.

There have been many more incidents throughout this year alone that cannot be recounted here. But one thing is clear: the Chinese working class is edging ever closer to tremendous events. At some point it will inevitably place its stamp on history. As the crisis of capitalism deepens inside China, more people will be pushed onto the streets to express their anger. The pressure on ordinary workers and youth are already unbearable. Sooner or later, the masses will be forced to take the road of class struggle.

The 20th Party Congress shows that the CCP administration under Xi is conscious of the potential for class conflict that is developing within Chinese society and will desperately attempt to prevent such a development. The criminal clique siding with Xi Jinping, however, will eventually discover that no matter how much power they have concentrated in their hands, it will be no match for the Chinese working class once it embarks on the road of class struggle.